Perhaps some of you were able to view all or part of this past Sunday morning service at the “Mother Emanuel” AME Church in Charleston, SC, where the horrific shooting took place last week. I followed most of the service and want to comment on the content.

Perhaps some of you were able to view all or part of this past Sunday morning service at the “Mother Emanuel” AME Church in Charleston, SC, where the horrific shooting took place last week. I followed most of the service and want to comment on the content.

First, if you do not know, the AME (African Methodist Episcopal) church has been a national presence since late in the 18th century. It has largely served the black community, first populated by free blacks before the Civil War and since then has of course had open doors to all. It might be termed a “freedom” church in that it has functioned as a place where blacks could have full expression of their religious beliefs and practices without harassment or repression from whites. Worcester has an AME congregation on Belmont Street, near the overpass with 290.

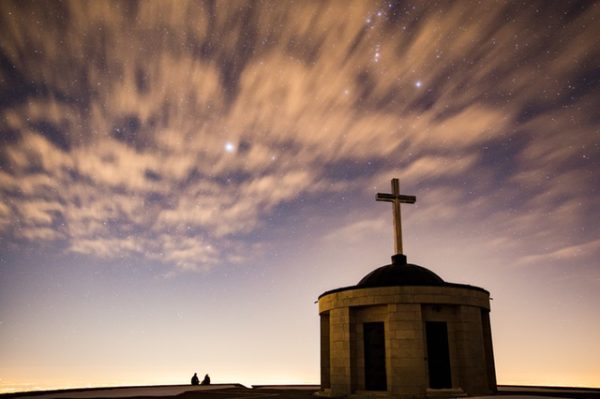

As I listened to the service Sunday, the first thing I felt was how powerfully the Church, and by this I mean the whole body of Christianity, can speak in a time of challenge and crisis. What happened just a few days before created an unspeakable moment. Yet those assembled in that church, and joined with many others in that one community who all tolled their bells at a common time, found a way to rise above the immediate devastation of lost lives and the sense of hollowness and impotence that created, and reveal a resilient, unrelenting faith that upheld them and stood as a bulwark against the tide of evil that had been unleashed in their midst. As vilely consuming as all that had occurred was, something else transformative and powerful was at work in that congregation that day.

When I was a theology student in Chicago, I attended some “black” services run under the auspices of Jesse Jackson. I remember thinking at the time how “eschatological” those services were. By that I mean they emphasized deliverance from current pain and injustice in some future age. They emphasized the notion that God stands alongside the downtrodden and will someday bring restitution and balm to those now bereft of it. Certainly the black community in American history has been down trodden in a way that few apart from that community can understand. The phrase “institutional racism” is not just an academic term; it is a reflection of a centuries-long plight of a group of people. And that fact I think, explains in large part the reason why the service at “Mother Emanuel” was so moving. The people attending were present out of deep need, longing, anguish, and grief. The moment might have been immediate, but the experience has repeated itself over generations, and they responded as they always have when set upon, in praise and reaffirmation of a timeless faith. They returned to hear, and hear again, the verities and precepts of a sustaining faith. Religious expression for communities of exclusion is a central pillar on which they rely when all else seems barren.

Some of the commentators whom CNN (the channel I was tuned to) asked to narrate observed that the black tradition has a way of celebrating joy that is different from expressing happiness. There could be no happiness in Charleston, or anywhere else in this country where caring people were dwelling this weekend past, but that body of believers assembled in Charleston showed us all how to be forward looking and joyful. That confidence within the people of “Mother Emanuel” was based upon an unwavering belief in an ultimately good, triumphant, and ever-resurgent God who, in their tradition, they know has always and unfailingly stood alongside them in times of distress.

We are struggling with tired forms, hollow liturgies, isolated pulpits, and empty pews in many of our churches today. The old patterns and traditions do not seem to speak meaningfully to many people. Yet, what I heard in that service from Charleston was very familiar in terms of content and form, and it was profoundly meaningful. The sequence of the service, the words of the prayers, the chosen scriptures, the hymn tunes, were all like kin to me. The preaching in terms of content was much the same as I would evoke, although as is characteristic of the black tradition, there was much more interaction between the preacher and the congregation than most of us are used to. Even the pianist participated in the spoken word as he or she, spontaneously it seems, reacted to various points of the sermon by playing bits of a melody or just a literal tinkling of the keys.

So I am prompted to ask the question, what is the difference that a church like “Mother Emanuel” could present so vitally when we, meaning a whole host of established but languishing congregations, cannot? The answers are myriad and delving into them would diminish the esteem I want to convey about the service Sunday, but one short answer is that we are lacking passion. God’s attentions I believe are most sought after and called for by those who live on the edges and who have no choice but to cry out in need. The “Mother Emanuel” congregation fully engaged the moment Sunday because the people needed to cry out for God’s attention. Born as it was, yes in all likelihood, of a deranged mind, but a mind that nonetheless was steeped in the vaporous kerosene of bigotry and prejudice. The poisons of such bigotry and prejudice are well understood and experienced by all discriminated groups of people, and they know one antidote that is stronger than all others, the power of a redemptive faith.

To conclude, I would say that passion comes from a sense of awareness that there is a struggle at hand, literally between the forces of good and evil, and that if in our complacency, our comforts, our studied indifference, or failing to see joy apart from happiness, we have muted ourselves to the reality of the presence of evil in our world, and our role in combating it, then we will have also denied ourselves access to the fervent, “eschatologically” grounded faith that so powerfully expressed itself in Charleston Sunday past.